Venice Architecture Biennale curator, Lesley Lokko, has added a shading device to the front of the Central Pavilion, that toys playfully with an informal building material well-known in Africa, sheet metal.

I have been coming to the Venice Architecture Biennale for a decade and a half and never have I ever seen this many women architects and architects of color represented. Ghanaian Scottish architect and educator, Lesley Lokko, the first Biennale curator of African origin, has put action behind her words. “The vision of a modern, diverse, and inclusive society is seductive and persuasive, but as long as it remains an image, it is a mirage. Something more than representation is needed, and architects historically are key players in translating images into reality.” (Quote from the Biennale website)

The title of the Biennale is “Laboratory of the future.” It includes 89 participants, over half of whom are from Africa or the African Diaspora. The gender balance is 50/50, and the average age of all participants is 43, dropping to 37 in the Curator’s Special Projects, where the youngest is 24. 46% of participants count education as a form of practice, and, for the first time ever, nearly half of participants are from sole or individual practices of five people or less. Across all the parts of The Laboratory of the Future, over 70% of exhibits are by practices run by an individual or a very small team.

Lesley Lokko in an interview stated that, “The dominant voice has historically been a singular, exclusive voice, whose reach and power ignores huge swathes of humanity—financially, creatively, conceptually—as though we have been listening and speaking in one tongue only. The story of architecture is, therefore, incomplete. Not wrong, but incomplete. It is in this context particularly that exhibitions matter.”

Lesley Lokko’s own project, an enmeshed map containing fragments of every participant in the exhibition. “Part canopy, part plan, the installation invites the audience to make new connections between participants, spaces, ideas and forms,” much like the whole Venice Biennale does. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

The thinking and impact of the curator, Lesley Lokko, to address this incomplete narrative is most manifestly present in the two main exhibitions, in the Central Pavilion in Giardini, and in the Arsenale.

The Force Majeure section, in the Central Pavilion in Giardini, gather 16 practices that represent a distilled force majeure of African and Diasporic architectural production. It is an exhilarating assemblage of work including Burkinabe architect Francis Kéré, the first Black winner of the Pritzker Prize (2022), and Ghanaian English architect, Sir David Adjaye, the first Black winner of the RIBA Gold Medal (2021).

Francis Kéré’s installation, named Counteract, is a curved clay wall showcasing visuals depicting remarkable instances of Sudano-Sahelian architecture. The project provides context to the past and potential future of West African architecture by exploring three aspects: What Was, What Is, and What Can Be. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

The Adjaye Futures Lab features a field of physical models paired with narrative films. The selected projects showcase narratives that emerged outside of the dominant canon, such as the Thabo Mbeki Presidential Library and its precolonial inspiration, and the Edo Museum of West African Art/Creative District, which aims to reconstruct, resurrect, and reposition ancient Benin City as a powerhouse of cultural output. As Adjaye Associates state, “These are narratives that speak to an ongoing quest to define, amplify, and encourage diasporic connection and cultural production.” (Quote from the Biennale website)

Model of Adjaye Associates project for the Newton Enslaved Burial Ground Memorial, Barbados, one of a series of models Adjaye is showing in the Central Pavilion. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

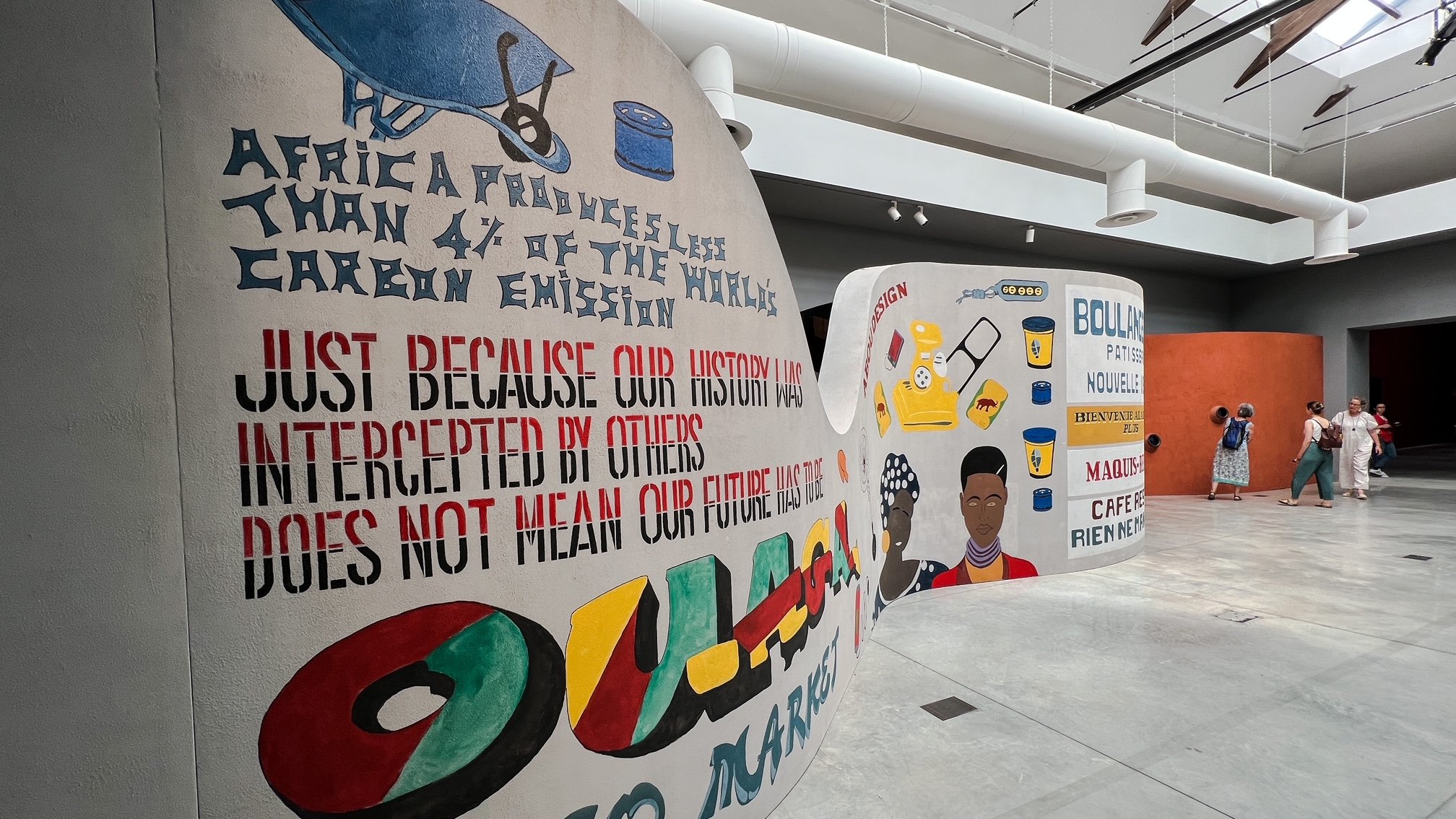

Kwaeε, Adjaye Associates installation outside the Arsenale, is made entirely of timber, that take on the qualities of its namesake, which translates as "forest" in Twi, one of Ghana's main languages. The installation is envisioned as a space for both reflection and active programming. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

(Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

I also found the projects by Atelier Masomi (run by architect Mariam Issoufou Kamara in Niamey, Niger, and Washington D.C., USA), by Hood Design Studio (Oakland, USA), by Urban American City (Toni L. Griffin, New York, USA), and by MASS Design Group (by Christian Benimana, Kigali, Rwanda) to be very interesting.

Atelier Masomi, by Mariam Issoufou Kamara: “To make architecture in a context of scarcity, extreme climate and economic vulnerability, we rely on a process to bring local narratives to the fore, translating dispossessed identities and history into architectural form. We call this approach Process.” (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

(Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

Hood Design Studio show ‘Native(s) Lifeways’, a project for the Black cultural landscapes of Charleston, South Carolina, both inside the exhibition as well as in the Scarpa Garden. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

Land Narratives - Fantastic Futures, by urban american city (Tony L. Griffin) gives voice to Black space and cultural practices, joys, and dreams of eight Chicagoans from the Chicago South Side through collages, mapping, film and voice-generated 3d clay objects. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

Afritect, by MASS Design Group, introduce a new generation of African architects to the world who focus on solutions and ideas that are simultaneously genuinely African and globally inspiring. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

Theaster Gates Studio (Chicago, USA) offers a respite from the chaos that such an exhibition also is with his documentary film Black Artist Retreat: Reflections on 10 Years of Convening (2023). In this film Gates demonstrates the complexities of the very notion of Black space, and the ways in which temporal Black spaces can be built to advance the cause of the arts and convene artists of color in a self-determined manner. If you visit, I encourage you to sit down and take part in this meditation on possibilites.

PS: In Venice, Theaster Gates Studio is also part of the exhibition, ‘everybody talks about the weather’ at the Fondazione Prada, with a video project, The Flood. ‘everybody talks about the weather’ is a research exhibition exploring the semantics of “weather” in visual art, taking atmospheric conditions as a point of departure to investigate the emergency of climate crisis, and definitely worth seeing if in Venice.

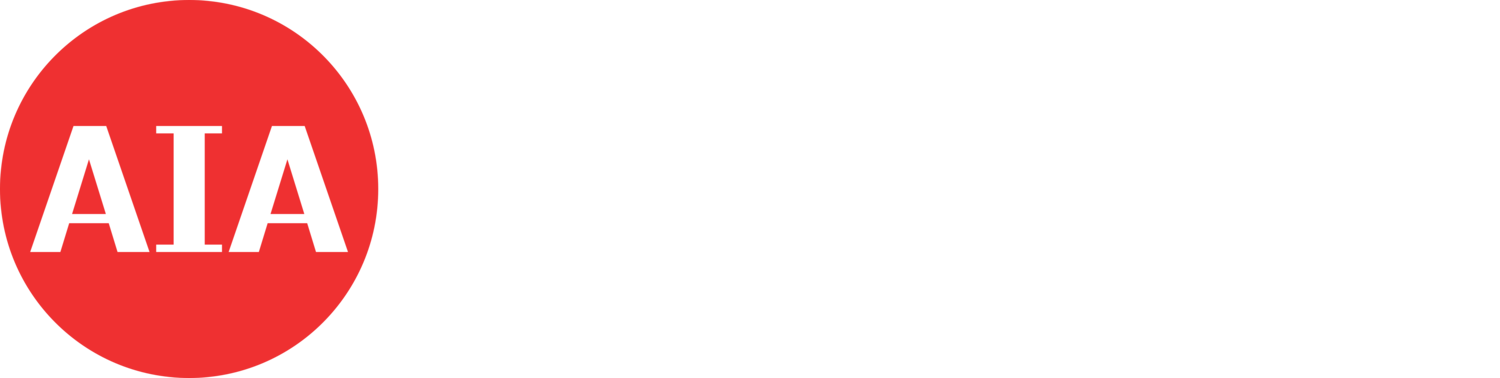

Finally, in this section is also the winner of the Silver Lion for promising young participant, Nigerian born Olalekan Jeyifous (Brooklyn, USA) and his project ACE/AAP, a make-believe lounge for the All-African Protoport, an imaginary sustainable transport network created by the collaboration of decolonized states in Africa. It is a bold and colorful and optimistic vision of a post-independence and self-sustaining Africa.

Olalekan Jeyifous is showing his make-believe lounge for the All-African Protoport. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

(Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

The Laboratory of the Future exhibition continues in the Arsenale complex, featuring the participants in the Dangerous Liaisons section and the Curator’s Special Projects section. The 37 practitioners chosen for this section all work in hybrid ways, across disciplinary boundaries, across geographies, and across new forms of partnership and collaboration.

Finally, the Guest from the Future section, features 22 emerging practitioners of color exhibited in both the Central Pavilion and the Arsenale.

There is so much to see and ponder and experience, that I cannot do it justice in this blog entry. Suffice to say, this is one of the most exciting architecture Biennale ever.

Look out for the second part of my exploration of this year’s Venice Biennale in an upcoming blog entry.

Henning Martin-Thomsen, Arkitekt MAA, Int’l Assoc. AIA, MMD (CBS)

Publisher and contributor to AIA International Communication & PR Committee

Francis Kéré’s installation. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)